When I first arrived in Tanzania I had planned to take the western road to Rwanda, along the shore of Lake Tanganyika, via Kigoma. But the rains have come late this year and the road is closed; impassable with thick mud and impromptu rivers. So I had ridden east to Iringa, planning to head north to Dodoma and then to cut back on myself and head north west to Rwanda, across the Wembere Swamps and the dusty north-western plains past Nzega. I am in a little café in Iringa staring at the map. It is a long detour. A huge > across the heart of Tanzania and the road will be desolate. I must stock up with food and water here.

A young guy pulls up a chair next to me and looks down at the map, which is splayed out beneath a mug of black tea on the wobbly table. I show him where I will go and he shakes his head solemnly and tells me I must not go this way. When I tell him I am on a bicycle, alone, he becomes more animated. He says there are bad men with guns on the north western road. Bandits from Rwanda. It is already late afternoon and I had planned to leave early the next morning. I ask him how he knows this and he says he is from Nzega. He knows the road well. I walk into a little tour company across the street and ask the travel agent about the route. He says the same. The road is dangerous. I must carry on east and reach Rwanda via Uganda.

I think back to when I met Jean-Claude in Livingstone, Zambia. He was scrawny and weathered with skin like burnished leather and thin grey hair. He told me how when he couldn’t get a visa to ride through Angola he had bicycled 2000 km across western Congo. He would not have been put off by the hearsay of a couple of local guys. By the remote prospect of trouble. I tell myself I will go on as planned and then change my mind. I know in daylight, riding, the warnings will fade in the sunshine. I know when I am camping on the dark roadside the spectre of trouble will rise out of the shadows and make me lonely and scared. I look at the map again and draw a line east to Dar Es Salaam. 400 km of main highway; of guesthouses and passing trucks and occasional road-trippers waving from battered Land Rovers. I will go to Dar and then north to Kenya, and across Uganda to Rwanda.

The next morning I rejoin the Tanzam highway and set off towards the eastern shoreline. It is a beautiful day. The wind flows lightly on my back while the sun climbs quickly above the receding bank of eastern cloud. After a long winding descent the road stretches out through the flat Tanzanian prairies, across miles of Khaki grasses and wide topped acacias, which spread out across the horizon in every direction, broken only by the occasional hump of a freestanding green hill that protrudes gently out of the bush. Soon the foothills of the Udzunga Mountains flank the road to the south and I am passing through a great valley filled with thousands of baobab trees. Those nearest the road loom powerfully out of the dust, casting tangled patches of shade on the flat tar. The upper branches flow from the stout trunks like locks of frozen hair, towering above the dried mud shacks that are dotted through the forest. I camp in the valley on the bank of the Ruaha River. In the moonlight the trees grow larger, their silhouettes bearing down from the starry sky, shrouding the valley floor in ghostly shadows.

I take two days to ride the 190 km to Morogoro across the Uluguru Hills and on through Mikumi National Park. On the roadside lime green cactuses and half built brick houses are interspersed amongst the bright fields of sunflowers and endless maize. Maasai in red and purple robes, with gapping round holes in their ear lobes, lead small herds of cattle through the scrub with tall staffs. Shortly after leaving Mikumi I ride past a sign marking the entrance to the Park. The bustle of passing bicycles and droning scooters and running children has stopped and the road feels very empty. I quicken my pace and scour the grasses for signs of animals. After 20 km I reach a small hut and am stopped by a warden. He tells me cycling in the Park is strictly prohibited, but, in this instance, as I have got this far, as my bicycle is strong, I may go on. As I pedal off he shouts that he will pray I do not encounter any lion or buffalo. The grasses are high and little pools of stagnant water sit in muddy enclaves off the road. The noise of the chain whirring as I ride startles a warthog who bursts from the grass towards the bush. A small herd of buffalo are sitting beneath a tree to my left. My eyes are fixed on them as I pass but they take no notice. After 50 km I make it out of the Park and reach Morogoro by lunchtime.

I leave Morogoro heading for Chimala, from where I will ride to Dar. There is a tall escarpment running parallel to the south. Frail trees are perched on its narrow ridge above a thick band of light cloud. The road is busier as I head east and it starts to rain. Lorries trundle past whipping up dark highway water from under their heavy wheels. It is muggy in Chimala and the rain has churned the verge into a thick brown paste. I sit down in a truckers bar and watch cradle shaped pens full of chickens being loaded onto a bus. The bar girls pull up chairs and sit staring at me while I write. I slowly list the countries I have passed through and they laugh and poke my legs and point at the bicycle behind. The sit with me for hours saying words I cannot understand and laughing with instinctive friendliness. When I come back later to eat, they are watching a trashy American sitcom called ‘Shades of Sin’ although none of them speak a word of English.

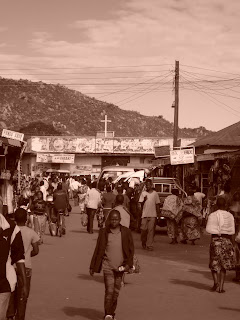

The next day I reach Dar Es Salaam in the late morning and dart through the chaos of the city’s choking roads. Combi’s cut me up and I swerve and brake and swear my head off and the driver looks perplexed and hits the side of the van through the window and honks his horn and then a gap in the traffic opens up and we both potter off into the smog. Swirls of dust rise from the wake of the rushing cars and I squint in the grime, dripping with sweat. Outside a Pepsi stand a guy strangles a dog with both hands; yelps and howls carry desperately across the roaring traffic and while I watch the man giggling I ride into a deep pothole and nearly come off. After hours of muddling my way through the city I arrive at the calm leafy driveway of the house I will stay at for the weekend.