I have been off the bike for over two weeks waiting for my visa, and I am jumpy as I swerve and dash through Nairobi’s morning traffic. My mind is already turning to where I will spend the night; thoughts that before the lay-up wouldn’t have bugged me. The uncertainty of the road ahead makes me sad.

I am heading west on the road to Uganda and soon after leaving the city I am climbing through the lower folds of the Rift Valley’s eastern edge, past empty fields towards distant hills. The sky is pale and blue and fine wisps of smoky cloud flutter across the horizon. The road is quieter here and I can see Lake Naivasha gleaming calmly and Mount Longonot rising from the flat valley floor. The descent into the valley is long and fast and I glide quickly through the breeze. Along the valley floor murky yellow grasses stretch out towards the southern hills beneath billowing Candelabra trees and lonely corrugated shacks. After a few miles the road climbs again and the pedals grind reluctantly as I make my way slowly up and up the oncoming hills. The sun is strong now and I pull into a little motel at a town called Gilgil and spend the afternoon reading in the shade.

The next day I rejoin the highway and ride 160km to Kericho. It is just light as I set off and the dull grey forms of far-away hills fade into the soft dawn sky as I descend towards Nakuru. I pass lakes, and tall, sprawling acacias, and little villages of brick houses with metal roofs. Children in smart green uniforms wave as they walk to school and dalla-dallas and rumbling trucks rush past me on the worn asphalt. I stop for a plate of beef and ugali at a little junction town. Across the road women scrub clothes in plastic buckets amongst a cluster of faded white tents. I ask a guy in the café why they are living in tents. He says they lost their homes in the violence in 2007. They have lived like this since. I turn off the highway and climb across the highlands towards Kericho. The road is flanked by deep green fields of tea; sprawling, well kept plantations that fan out over the smooth hills in endless, orderly rows. Amongst the fields I pass big estates made up of little white rectangular houses, where the workers live. They are all identical, with two front windows and a wooden door between, planted like blocks of lego in the trimmed grasses. The road is full of holes and I slowly rattle across the potted tar under the afternoon sun, reaching Kericho at three.

I ride out of town at dawn and young women are already picking tea in the fields off the road. They stand above the short plants, like statues in the smoky mist, watching me pedal past. The air is cold and toddlers sit outside huts wrapped up in woolly hats and puffy jackets while their mothers boil up ugali in thick black pots over smouldering wood. I stop on a little bridge above a fast running stream and watch the sun rise over the tall forests that grow on the highest slopes around Kericho. I think that if I am riding towards Kisumu, and Uganda, the sun sould be rising behind me, not to the left. I ask a passer-by where this road goes to. He says Kisii, a town to the south. I have taken the wrong road. I take out the map and decide to carry on to Kisii and ride to Kisumu the following day. The road is quiet and the highlands beautiful, but it means a 150km detour.

I climb up, and freewheel down, hill after hill past steep sloping fields of maize and tea. On the roadside men sit chipping at blocks of stone with hammers and call out at me: ‘Sah, Sah, where to? Where from? How far? Some of them get up and shout: ‘Yes you can! Yes you can!’ with their hands raised above their heads. The hills grow steeper as the midday sun reaches its hottest and I am covered in sweat as I ride into Kisii. It is market day and large women lie in the dust under umbrellas behind piles of fruit.

The next day, after a couple of hours riding from Kisii, I emerge from the hills and the green lowlands unfurl before me, from the shores of Lake Victoria to a distant escarpment in the east. I can see for miles in every direction and it is a good feeling to ride across the open expanses, past little mud huts, through the swampy flats. It is Sunday and clapping and singing and a preacher’s booming voice carry to the road from a little white church. There are women sitting under trees selling yams in buckets. They will sit like this till dusk and I wonder if anyone will stop to buy yams today. As I near Kisumu a young guy runs after me shouting: ‘It is you. It is you. I read you in the newspaper. You are the one who rides his bicycle around the world. And now you are here in Kenya.’ I tell I am not and he looks disappointed. He says that guy must be very strong. It is quiet when I ride into Kisumu. On the main street bums sit on a corner flipping coins and drinking whisky. They peer at me riding past with junky eyes that look out above puffy cheeks. I see them later bedding down in a derelict stone building with no roof.

From Kisumu it is 120 km to Busia, just across the Ugandan border. On the way I stop for a drink at a village off the highway, called Sidindi. An old man sits on the step next to me. I give him a sandwich and he tells me this is the Luo region. He says Obama’s grandfather resides just a few kilometers behind here. He says Obama himself came to the region. He says that on the day of the election in the US, the village also put on an election. They made ballot boxes, one for Obama, and one for McCain. The whole village voted. Obama got all the votes and McCain got none.

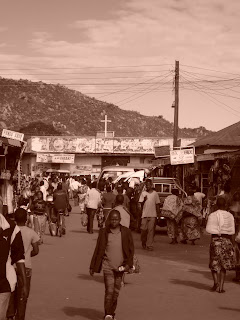

The road is flat and by lunchtime I am crossing the border. The customs officer stares at me and asks why I am so dirty. I tell her it is dusty and I am on a bicycle. She tells me to make sure I take a bath and change my clothes. Busia is full of people rushing back and forth; everyone sweating and in a hurry. I ride a couple of kilometers to the edge of town and sit writing under a tree. As the sun goes down the insects start to roar and bats swoop between the trees.